As a physiotherapist with a focus on hypermobility, it struck me the other day, can tendons be hypermobile? Indeed, researchers have found a link between one of the genes associated with Classic Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome and an increased risk of tendon injuries.[1]

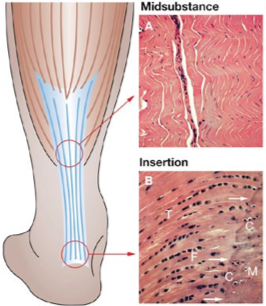

I did a little research and it turns out tendons can be “kind of” hypermobile. You see, hypermobility is defined as joints moving beyond normal range of motion and joints are passively held together with joint capsules and ligaments. Tendons, on the other hand, connect muscle to bone (figure 1) and are therefore not technically hypermobile because the term “hypermobility” refers specifically to the joints.

However… in hypermobile connective tissue disorders, such as Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome, it is the structure and function of the connective tissue proteins, such as collagen, that are the concern.[2] And while ligaments are about 85-90% (dry weight) collagen[3], tendons aren’t far off, being made of 60-80% (dry weight) collagen.[4,5]

Figure 1. The Achilles tendon (Riley, 2008, pg. 83)

Further, tendons cross over joints and hence if the joint bends further, the tendon stretches further. Therefore, it stands to reason that the tendons of hypermobile people carry a degree of structural vulnerability much like their joints and hence can be thought of as “kind of” hypermobile.

I do frequently see tendon injuries in my hypermobile patients and would therefore like to share three tips for taking care of your “hypermobile” tendons.

Tip 1: avoid doing too much, too soon

Most cases of tendon injury are associated with overuse.[6] Scientists have proposed that overuse, or “too much, too soon,” occurs when a person increases their weekly activity by more than 30% compared to the average of the previous four weeks.[7] In other words, if you usually walk 5000 steps per day, but increase to 7000 steps per day while on a holiday for a week, you have increased the load through your foot and ankle by 40% and have an increased risk of hurting your foot and ankle tendons.

While increasing the duration of physical activity is a risk factor, so too is increasing the intensity of physical activity. Tendons can handle slow movements better than fast movements.[8] Therefore, tendons can handle walking better than running.

That is not to say that you should only move slowly for the rest of your life, it is simply worth noting that it takes two to three days for a tendon to recover from high-intensity activity like running (assuming you haven’t injured your tendon).[9] So, if you currently run each week you do not need to give it up, simply leave two or three days between runs and only progress your running distance or speed by 10-20% per week to minimise the risk of an overuse tendon injury.

In addition to how much and what type of activity you chose, warming up prior to activity is also recommended to reduce the risk of hurting your tendons.[10] If I continue with my running example, warming up would involve walking for 5-10 minutes before you start running.

Tip 2: Be a little more careful if…

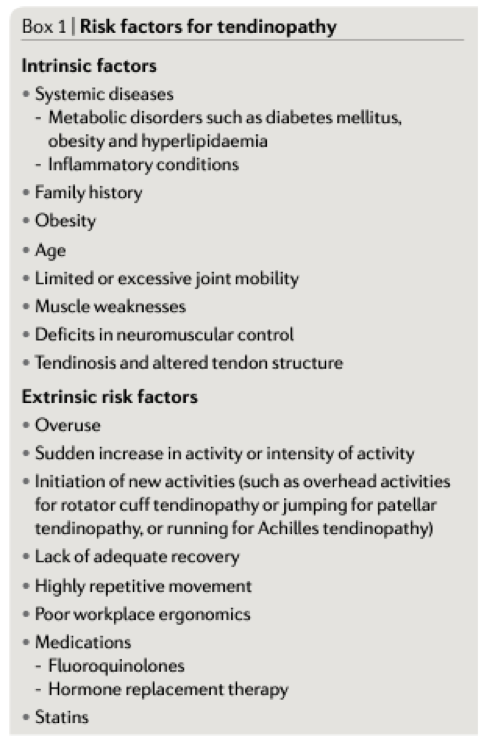

In addition to your “hypermobile” genes and your physical activity choices, there are a number of additional tendon risk factors to keep in mind when deciding how much physical activity to do.

Figure 2 outlines the medical conditions, behaviors, and medications that researchers have found increase the risk of a tendon injury.

Figure 2. Risk factors for tendon injury (Millar, 2021, pg. 4)

When it comes to my hypermobile patients, I am particularly mindful of the following tendon risk factors:

- Weakness due to prolonged periods of pain induced immobility

- Movement patterns that bend joints beyond normal range of motion and hence create more stress through tendons

- Impaired movement awareness resulting in less coordinated movement patterns that create more stress through tendons

- Co-existing autoimmune diseases

- Prolonged periods of impaired sleep leading to impaired collagen health[11]

If you note a lot of the above factors in yourself, I recommend you progress your exercise a little slower and allow a little more recovery time between exercise sessions.

Tip 3: Strengthen your tendons

While doing too much, too soon, will increase your risk of injuring your tendons, doing too little leads to tendon weakness. [8,12] Performing resistance training stimulates the cells in tendons to create a stronger collagen matrix and has been found to reduce the chance of tendon injury.[6,8,12, 13] When designing a tendon strengthening program the considerations are frequency, type, intensity and time.

Frequency:

Leave two days between your strengthening sessions.

Type:

Tendons particularly like slow and heavy resistance like that found in weights training.

Intensity:

While researchers have found that lifting a heavy weight that is at least 70% of the maximum weight you could lift for one repetition (1 rep max or 1RM) is optimal for strengthening tendons, when I looked closer at the research data I noticed some of the participants in the studies entered the “damage level” at 60% of 1RM[13,14] and that loads less than 70% 1RM have also been found to stimulate tendon strengthening.[8] Therefore, I recommend starting a strengthening program at 50-60% of your 1RM (I’ll discuss further in the example below).

Strengthening protocols often involve a slow movement that is 3-4 seconds up and 3-4 seconds down.

Strengthening protocols often use 2-3 sets of 8-15 repetitions.

Time:

While some studies have found tendons develop more strength after eight weeks of strength training, most research showing tendon strengthening went over at least 12 weeks.[8]

Example

Let me give you an example of what starting a tendon strengthening program might look like:

Let’s say that a hypermobile person is currently hiking three times per week and wants to add running two times per week in the upcoming warmer months. To reduce their risk of developing an Achilles tendon injury they decide to start an Achilles tendon strengthening program.

Frequency:

The person is going to perform their Achilles tendon strengthening program on Monday and Thursday each week.

Type:

Heel raise exercises off a step. (seen here)

Intensity:

To establish the starting point of their Achilles tendon strengthening program the person needs to determine their current 1RM. The person’s Achilles tendons have been used for hiking for many months, so they can perform slow heel raise exercises off a step without concern of increasing their Achilles tendon activity by more than 30%.

The person starts their 1RM assessment by conservatively warming up with 10 double leg heel raises off a step. That feels fairly easy, so they wait two minutes and then they perform their maximum number of double leg heel raises off a step at a pace of 4 seconds up and 4 seconds down. They perform 25 repetitions before the movement becomes too difficult to perform smoothly and completely.

The person then uses a 1RM estimation calculator online (like this: https://strengthlevel.com/one-rep-max-calculator) to determine their 1RM. The person weighs 100kg and performed 25 repetitions which equates to a 1RM of 183kg. The person’s 100kg body weight is therefore 55% of their 1RM and is therefore a good starting weight for their strengthening program.

For the first week of their strengthening program the person performs the double leg heel raise exercise for two sets of 15 repetitions with a two minute rest between sets. The person goes on to add 20% more repetitions or weight each week until they reach a plateau where they can’t increase any more without finding the exercise too difficult. They then maintain that intensity twice per week.

Time:

The person completes a full 12 weeks of the Achilles tendon strengthening program before they start their graded running program.

I appreciate that the above process is complicated. I recommend you see an exercise professional, such as a physiotherapist/physical therapist or a kinesiologist/exercise physiologist with an understanding of hypermobility to help design a strengthening program that suits your needs.

Want to read more of Aaron’s articles on EDS, click here.

- Kaya, D.O. (2020). Architecture of tendon and ligament and their adaptation to pathological conditions. In A. Salih & S. Ibrahim, Comparative Kinesiology of the Human Body: Normal and Pathological Conditions (pp. 115-147). Elsevier

- September, A., Rahim, M., & Collins, M. (2016). Towards an Understanding of the Genetics of Tendinopathy. Advances in experimental medicine and biology, 920, 109–116. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-33943-6_9

- The Ehlers-Danlos Society. (2024). What is EDS?. https://www.ehlers-danlos.com/what-is-eds/

- Naya, Yuki & Takanari, Hiroki. (2023). Elastin is responsible for the rigidity of the ligament under shear and rotational stress: a mathematical simulation study. Journal of orthopaedic surgery and research. 18. 310. 10.1186/s13018-023-03794-6.

- Kannus P. (2000). Structure of the tendon connective tissue. Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports, 10(6), 312–320. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0838.2000.010006312.x

- Riley G. (2008). Tendinopathy–from basic science to treatment. Nature clinical practice. Rheumatology, 4(2), 82–89. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncprheum0700

- Millar, N. L., Silbernagel, K. G., Thorborg, K., Kirwan, P. D., Galatz, L. M., Abrams, G. D., Murrell, G. A. C., McInnes, I. B., & Rodeo, S. A. (2021). Tendinopathy. Nature reviews. Disease primers, 7(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-020-00234-1

- Blanch, P., & Gabbett, T. J. (2016). Has the athlete trained enough to return to play safely? The acute:chronic workload ratio permits clinicians to quantify a player’s risk of subsequent injury. British journal of sports medicine, 50(8), 471–475. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2015-095445

- Lazarczuk SL, Maniar N, Opar DA, Duhig SJ, Shield A, Barrett RS, Bourne MN. Mechanical, Material and Morphological Adaptations of Healthy Lower Limb Tendons to Mechanical Loading: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. 2022 Oct;52(10):2405-2429. doi: 10.1007/s40279-022-01695-y. Epub 2022 Jun 3. PMID: 35657492; PMCID: PMC9474511.

- Gabbett, T.J., Oetter, E. From Tissue to System: What Constitutes an Appropriate Response to Loading?. Sports Med (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-024-02126-w

- Sople, Derek & Wilcox, Reg. (2024). Dynamic Warm-ups Play Pivotal Role in Athletic Performance and Injury Prevention. Arthroscopy, Sports Medicine, and Rehabilitation. 101023. 10.1016/j.asmr.2024.101023.

- Chang, J., Garva, R., Pickard, A., Yeung, C. C., Mallikarjun, V., Swift, J., Holmes, D. F., Calverley, B., Lu, Y., Adamson, A., Raymond-Hayling, H., Jensen, O., Shearer, T., Meng, Q. J., & Kadler, K. E. (2020). Circadian control of the secretory pathway maintains collagen homeostasis. Nature cell biology, 22(1), 74–86. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41556-019-0441-z

- Stańczak, M., Kacprzak, B., & Gawda, P. (2024). Tendon Cell Biology: Effect of Mechanical Loading. Cellular physiology and biochemistry : international journal of experimental cellular physiology, biochemistry, and pharmacology, 58(6), 677–701. https://doi.org/10.33594/000000743

- Merry, K., Napier, C., Waugh, C. M., & Scott, A. (2022). Foundational Principles and Adaptation of the Healthy and Pathological Achilles Tendon in Response to Resistance Exercise: A Narrative Review and Clinical Implications. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 11(16), 4722. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11164722