In a recent article published in the Scandinavian journal of Primary Health Care, a group of doctors and medical researchers encouraged the medical community to re-evaluate how we approach care for people with Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS). [1] The authors proposed that based on the current evidence, CFS is not an incurable disease, but rather an innate defensive response that can be resolved.

As I understand it, the CFS “defensive response” is activated when the accumulation of biological, psychological, and social stressors or “threats” outweigh “bio-psycho-social safeties” over a prolonged period of time. For example, during the Covid-19 pandemic a person may have been particularly anxious about contracting the virus (psychological distress), been socially isolated due to this anxiety and societal changes at large (social distress), and then become ill with the virus (biological distress). In this example, the accumulated bio-psycho-social distress results in hormonal, immune, and neurological changes sufficient to push the person’s system into a CFS response.

With the physiology associated with these biological, psychological and social “threats” in mind, the authors suggest that rather than responding to CFS with more physiological “threats,” such as inactivity, social isolation, and a fear-inducing “incurable” label, the best course of action is for healthcare providers to support the sufferer with guidance on how to gradually return to activities of wellness, value, purpose, and connection. In other words, the advice to date has been to combat CFS with defensive strategies, but these doctors are suggesting that to win your battle against CFS you need to play both defense and offense.

The pertinent question then becomes, what is the right balance of defense and offense? Another group of doctors and medical researchers has proposed a ‘dispositionalism’ approach, which combines both ‘defense and offense’ strategies to help manage persistent physical symptoms, such as chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS). [2]

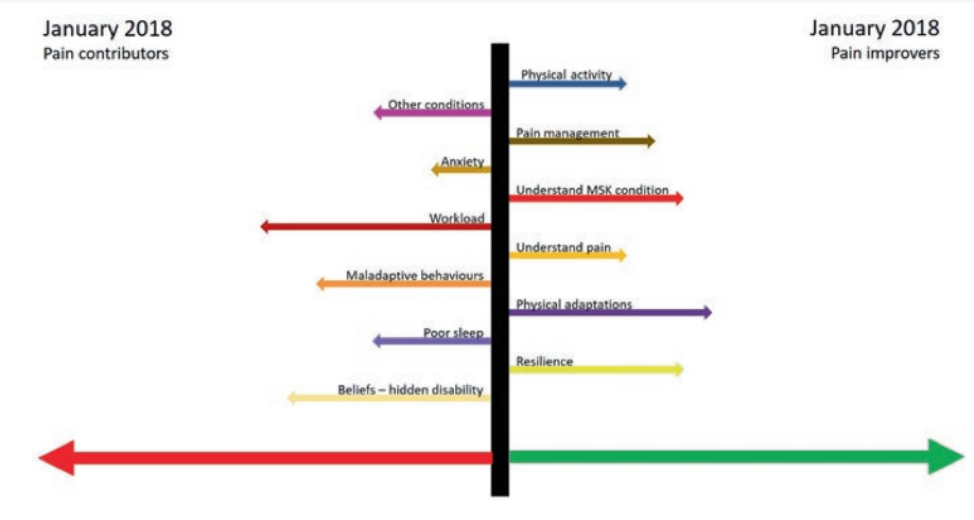

Essentially, the aim is to reduce “bad” dispositions (play defense) and increase “good” dispositions (play offense) until you shift your stress physiology sufficiently away from the symptomatic threshold.

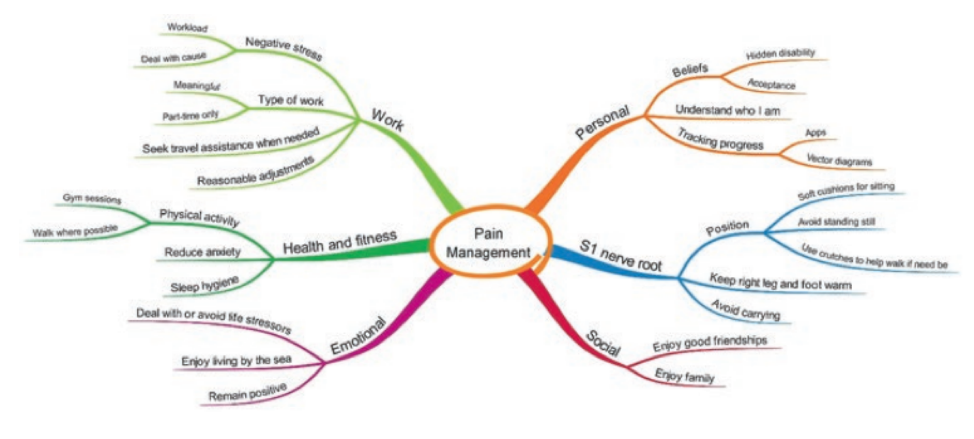

The authors of the dispositionalism approach provide an example of how you would apply this theory to a chronic pain condition (figures 1 and 2). Even though the figures reference pain, you can equally apply the same principles to fatigue.

Fig. 1 An example of a mind map illustrating various stressors (Price, 2020, p. 124)

Fig. 2 An example of a graph illustrating the balance of various stressors (Price, 2020, p. 125)

From a physiotherapist/physical therapist perspective, the takeaway from this insight is that how a person with chronic fatigue feels physically is not just about their physical activity. Therefore, my role is to help find physical activity that is both physically safe and enriching.

The authors of the Scandinavian journal of primary health care article emphasized that their motivation in writing their article was to shift the discouraging medical narrative around CFS to a more hopeful one. They highlight that people can recover from CFS. I echo this message of hope. I have seen people with hypermobility recover from CFS.

For me, two recent examples of hypermobile people recovering from CFS come to mind. In both situations, the people were diagnosed with long COVID induced CFS.

- Both had been bedridden for an extended period of time.

- Both gradually return to activities of daily living.

- Once they could function in their home, they came for physiotherapy/physical therapy. They both started conservatively with physical activities they previously enjoyed.

They both experienced slow progress, but interestingly, after a number of months, both these people experienced a significant turning point. One discovered that adding some “offense” in the form of positive social interaction significantly improved their ability to participate in physical activity. The other person discovered that adding some “defense” in the form of removing toxic social influence and removing toxic self-talk significantly improved their physical abilities.

Following their respective epiphanies, both people experienced a steep improvement in their symptoms and went on to returned to normal life. To be clear, I am not saying their symptoms were simply psychosomatic, I am simply pointing out that positive physiology can be triggered from a wide range of bio-psycho-social variables. I am also saying that recovering from CFS is possible.

Want to read more of Aaron’s articles on EDS, click here.

- Oslo Chronic Fatigue Consortium, Alme, T. N., Andreasson, A., Asprusten, T. T., Bakken, A. K., Beadsworth, M. B., Boye, B., Brodal, P. A., Brodwall, E. M., Brurberg, K. G., Bugge, I., Chalder, T., Due, R., Eriksen, H. R., Fink, P. K., Flottorp, S. A., Fors, E. A., Jensen, B. F., Fundingsrud, H. P., Garner, P., … Wyller, V. B. B. (2023). Chronic fatigue syndromes: real illnesses that people can recover from. Scandinavian journal of primary health care, 41(4), 372–376. https://doi.org/10.1080/02813432.2023.2235609

- Anjum, Rani Lill & Copeland, Samantha & Rocca, Elena. (2020). Rethinking Causality, Complexity and Evidence for the Unique Patient A CauseHealth Resource for Healthcare Professionals and the Clinical Encounter: A CauseHealth Resource for Healthcare Professionals and the Clinical Encounter. 10.1007/978-3-030-41239-5.