As a physiotherapist/physical therapist with a focus on hypermobility, I often have patients who are understandably worried they may have upper cervical instability (UCI)/atlantoaxial instability (AAI) (different terms for the same thing) or craniocervical instability (CCI). In the hope of providing a concise and easily understandable overview of what I have learned about the diagnosis of UCI/CCI, I share the following.

What is UCI/CCI?

UCI/CCI are terms used to describe when the bones at the base of the head (cranium) and or the bones at the top of the neck (cervical vertebrae or Atlas-C1 and Axis-C2) shift in a way that results in the brain stem and upper spinal cord to become “squished.” Let me show you what I mean.

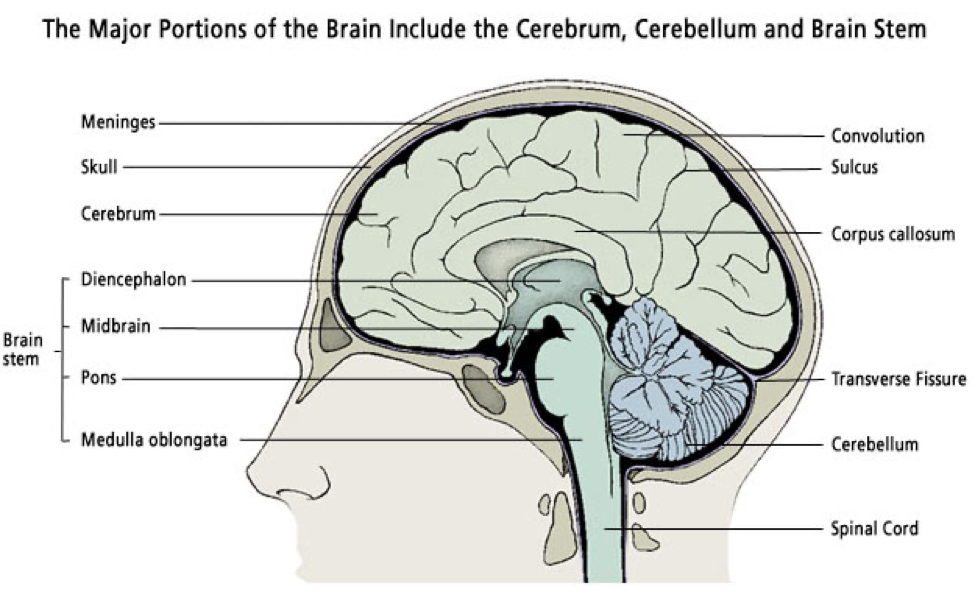

Figure 1 shows what we would expect to see in a normal stable head and neck. You can see that the bottom of the brain stem (medulla oblongata) flows smoothly into the spinal cord without interruption.

Fig. 1 – (Medika Life, 2020)

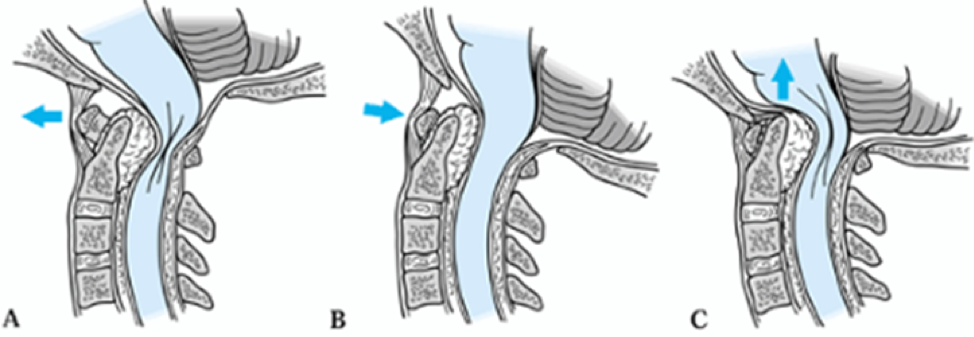

In contrast, Figure 2 shows three close-ups of where the cranium sits atop the upper cervical spine and highlights two different ways instability can result in a squished brain stem and spinal cord. In “A” the brain stem and upper spinal cord are being squished by the C1 vertebra (or Atlas) moving too far forward as the head nods forward. In “B” the brain stem and upper spinal cord are not squished as the C1 moves back as the head tilts back. And in “C” the brain stem is squished because the head has sunk into the top of the neck.

Figure 2 – (Teach Orthopedics, 2024)

The consequence of this “squishing” of the brain stem and spinal cord may be a combination of the following symptoms:

- Headache

- Neck pain

- Numbness and weakness in the arms, hands, and legs

- Dizziness/vertigo/imbalance

- Visual disturbances

- Difficulty swallowing or speaking

- Memory and concentration problems

- Shaking episodes

- Fainting

- Fatigue

I highlight “combination” because while head and neck pain are the most common conditions people come to see me with when they ask me about UCI/CCI, in a recent article written by experts from The National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London, the doctors question whether you can accurately diagnose UCI/CCI if the only symptoms are head and neck pain. I’ll discuss further below.

How is UCI/CCI diagnosed?

Firstly, I should point out that a medical expert, such as a specialist neurosurgeon, makes the diagnosis of UCI/CCI, not a physiotherapist/physical therapist, so please do not look at this blog post as a replacement for consulting a medical expert.

As you’ll remember from the diagrams above, UCI/CCI are bones moving too far resulting in the brain stem and spinal cord getting squished. The following examination techniques are looking for evidence that suggests this is the case.

One way doctors can look at how far the bones move is by taking pictures with an X-ray or MRI machine. You’ll recall from my description above that the position of unstable bones depends on the position of the head, so the X-ray or MRI pictures are taken while the person is upright with the head nodding forward and then the head tilting back. The doctor measures how far the bones are moving relative to each other on the X-ray or MRI pictures. If the bones are found to move a sufficient distance then this is considered evidence that UCI/CCI is taking place. An X-ray will only show the bones, whereas an MRI will also show the brain stem, spinal cord, and overlapping conditions, such as a Chiari malformation, so an MRI may be more accurate.

In addition to X-ray or MRI picture analysis, the doctor will also perform a physical examination looking for signs of neurological deficiency. Neurological deficiencies can include weakness and or a loss of sensation in the person’s tongue, throat, neck, arms and legs. Neurological deficiencies suggest the nerve signals traveling from the brain through the brain stem to the face and body are not getting through properly (in other words, the brain stem may be getting squished).

In addition to measuring the bone movement on the pictures and testing for a loss of sensation and movement, the doctor might also check certain reflexes, that if present, suggest there is interference in the nerve signal. It is the combination of both the pictures and the physical examination findings that are used by the doctor to support their diagnostic theory that the person has UCI/CCI.

Finally, the doctor might want to check whether the person’s problems improve if they wear a ridged neck brace that supports the head and neck and hold them in alignment (see figure 3). Theoretically, if the neck is being held straight by the brace, the brain stem and spinal cord will not get squished and the person’s nerves should work better and the person should therefore feel better.

If a person demonstrates sufficient findings across all these tests, the doctor may make the diagnosis of UCI/CCI.

Figure 3

Miami J Collar

Aspen Vista Collar

Why is there some controversy surrounding the diagnosis of UCI/CCI?

Firstly, it is worth saying that there is not always controversy with the diagnosis of UCI/CCI. I have had patients who shared their stories of presenting to the emergency room with symptoms that sounded like they were having a stroke and they underwent emergency surgery for UCI/CCI and this surgery resolved or stabilised most of their symptoms. But, in the absence of significant neurological deficits, for example, if head and neck pain are the only symptoms, the diagnosis of UCI/CCI may be controversial. This controversy is discussed by Dr. Mehta and his colleagues from The National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London in this article.

Dr. Mehta and his colleagues express the following concern:

“There is no way to differentiate between hypermobility and instability”

Let me explain:

People can have hypermobile joints that are not causing them any problems (in other words, joints can be hypermobile, but not unstable). For example, I often see people bend their elbow in the wrong direction and have no pain doing so, or pop their shoulder in and out to show me the extent of their hypermobility and then use their shoulder after the spectacle without any problems. Additionally, I have seen patients that had MRI pictures confirming they have UCI/CCI or a Chiari malformation, yet they had no symptoms during our meeting. So, just because you see a joint move beyond normal range, doesn’t mean it is causing a problem.

An example of the challenge of differentiating between hypermobility and instability in UCI/CCI can be found in this article by two EDS experienced physical therapists, Susan Chalela and Leslie Russek. In this fascinating article, Chalela and Russek summarize the journeys of three of their patients who kindly shared their stories of suffering with UCI/CCI. The three people were diagnosed with UCI by an EDS neurosurgeon based on physical exam and upright cervical flexion/extension MRI (as I described above).

Chalela and Russek report that one person got sufficiently better without surgery, one person significantly improved following stabilisation surgery but continued to experience “occasional mild to moderate flares,” and the other person unfortunately did not improve following stabilisation surgery. The varied success of the stabilisation surgery demonstrated in this article highlights that UCI/CCI can be present, yet not the only cause of symptoms.

You may then ask, well if UCI/CCI was not the cause of the person’s symptoms, then what was? The answer to this question may be found in this article by an EDS specialist neurosurgeon, Dr. Henderson, and his colleagues. In this article, the researchers followed up with 53 people about a year after they had stabilisation surgery for their UCI/CCI to see how they were feeling. While 94% of the participants said they would have the surgery again under the same circumstances, and 75% reported significant improvement in their symptoms, 25% did not significantly improve. For this 25% that had ongoing symptoms, in the majority of cases, their symptoms were attributed to other co-existing medical conditions that were overlapping with their UCI/CCI. This 25% had an average of seven co-existing conditions each (table 6 in the article outlines the long list of co-existing medical conditions).

For me, these three articles by EDS experts highlight that even when examination is performed by a world leading expert, with the most advanced technology, showing all available due diligence, one can never be 100% sure that UCI/CCI is the cause of their symptoms until after expert administered surgery.

I have seen the understandable fear that the thought of having UCI has caused my patients. I have seen that fear increase disability and suffering. I hope the information I have provided above helps reduce any unnecessary fear in hypermobile people with headaches and no neurological deficiencies.

- Teach Me Orthopedics. (2024, Sep 17). Rheumatoid Arthritis of The Cervical Spine. https://teachmeorthopedics.info/rheumatoid-arthritis-of-the-cervical-spine/

- Chalela, S., & Russek, L. N. (2024). Presentation and physical therapy management using a neuroplasticity approach for patients with hypermobility-related upper cervical instability: a brief report. Frontiers in neurology, 15, 1459115. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2024.1459115

- Henderson, F. C., Sr, Schubart, J. R., Narayanan, M. V., Tuchman, K., Mills, S. E., Poppe, D. J., Koby, M. B., Rowe, P. C., & Francomano, C. A. (2024). Craniocervical instability in patients with Ehlers-Danlos syndromes: outcomes analysis following occipito-cervical fusion. Neurosurgical review, 47(1), 27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10143-023-02249-0

- Medika Life. (2020, Sep 30). Human Anatomy: The Brain. https://medika.life/the-brain/

- Mehta, D., Simmonds, L., Hakim, A. J., & Matharu, M. (2024). Headache disorders in patients with Ehlers-Danlos syndromes and hypermobility spectrum disorders. Frontiers in neurology, 15, 1460352. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2024.1460352