This is part three of a three part series, click here for article part one and part two.

Finding Your Way

As a physiotherapist, I often see patients who have had years of persistent pain. Many of them have never received a clear diagnosis despite having had numerous medical tests. They also tend to be unresponsive to nearly all of the treatments they have tried. According to U.S. research, these patients’ experiences with persistent pain are not rare. Approximately 20% of American adults have chronic pain[1], and research suggests that current treatments offered for chronic pain are, on average, not that effective.[2]

However, we know that some people with chronic pain do get better.[3] After my own 13-year bout with chronic back pain, I am better. In reflecting on my patients’ success stories and my own experience in overcoming chronic pain, I have come to the conclusion that overcoming chronic pain often involves a sequence of events, rather than a specific treatment.

The following three success stories illustrate how varied an individual’s recovery from chronic pain can be.

The case of the placebo effect

In 2007, I had surgery to repair a ruptured ligament in my right knee. After the surgery, the surgeon told me that I had a lot of cartilage damage in my knee. In the years that followed, the condition of both of my knees seemed to worsen. By 2014, my knees were cracking and painful with daily use, so I decided to see a Physiatrist, a medical doctor who specializes in physical medicine and rehabilitation.

The doctor examined my knees and decided to send me for an MRI (a medical imaging technique). At my second appointment, the doctor combed through the MRI images and told me “your knees are a mess”. He then elaborated on all of the parts of my knees that were damaged and inflamed. He recommended hyaluronic acid injections, which he told me worked by acting like a lubricant and shock absorber in the knee joint. To maintain the benefit of these injections, I would need to get my knees re-injected every six months. Based on his advice, I decided to get the injections.

After my first injection, I did a deep squat and was amazingly pain-free. I was sold. My knees felt the best that they had in years. What I didn’t realize at the time was that the hyaluronic acid injections were accompanied by lidocaine injections, a local anesthetic, that temporarily relieves pain.

For the next two years, I received these injections and I would tell people that the injections were the reason that my knees felt better. I could squat, run and jump, all without pain.

In 2016, I happened to be sitting next to an orthopedic surgeon on a two-hour flight. At some point in our conversation, the topic of hyaluronic acid injections came up. Without knowing that I had been receiving them, he tells me “they are just placebo.” I was shocked. But I didn’t doubt that he was telling me the truth. I knew enough about the science of pain through my own research that the placebo effect can be very real. I just never thought that it could happen to me!

I realized that the real reason for my pain-free knees – especially initially – was the combination of the lidocaine injections and my belief that my knees would be better as a result of the injections.

I decided to stop the injections. And my persistent knee pain never came back.

The case of the unhappy runner

A 20-year-old man came to see me with concerns of progressively worsening knee pain while running. He had seen an orthopedic surgeon who told him that there was nothing structurally wrong with his knees. I also couldn’t find any physical evidence of damage to his knees. He was clearly in pain, but I couldn’t find anything broken or inflamed. Based on his doctor’s advice, we started a strengthening program for his unexplained knee pain.

During our treatment sessions we discussed the complex nature of pain and I suggested to him that his knee pain might not be purely a physical problem. I told him that pain could sometimes be caused or aggravated by psychological factors such as stress. He seemed skeptical of my opinion but continued to see me a few more times in order to finalize his home exercise program. Unfortunately his knee pain didn’t get any better.

Two years later, I was working in a different country and my clinic received an email from this man. He wanted to tell me that although he didn’t believe me at the time, he had never forgotten our conversation. He told me that as his knee pain had worsened, he decided to explore possible psychological contributors to his pain. In particular, he told me that he had read Dr. John Sarno’s book, The Mindbody Prescription: Healing the Body, Healing the Pain[4], and acknowledged that there were emotional components underlying his pain. He told me that after reflecting on the book, he made some life changes and was now running pain-free.

The case of the family reconciliation

My colleague was going away for several weeks and wanted me to see her patient who had been diagnosed with “frozen shoulder”. The patient shared her experience of right shoulder pain with me from the previous nine months. She told me that her shoulder felt very tight and was painful despite physiotherapy and a cortisone injection that she had received approximately three months after her initial diagnosis. She told me that she was going to receive another cortisone injection before taking a short trip, and would see me again in two weeks.

When I saw the patient two weeks later, she threw her right arm up over her head in a triumphant wave and said, “I’m all better – the second cortisone injection did the trick.”

When I told my colleague of her patient’s miraculous recovery she was very surprised; her patient had not had any response to the first cortisone injection she received. Moreover, my colleague knew – as did I – that research had found that cortisone injections for frozen shoulder are only slightly better than placebo, provide only short-term relief and are most effective in the first six months of developing a frozen shoulder.[5] In other words, it didn’t make sense that this patient would be better as a result of the cortisone injection.

As it happened, the cortisone injection coincided with a personal trip by the patient to reconcile a family dispute. My colleague and I both agreed that because of the multidimensional nature of persistent pain, there was likely a significant emotional component to the patient’s pain. It was even possible that she didn’t actually have a true frozen shoulder. Whatever the cause, her pain was gone and she was able to move her shoulder freely again.

How to make sense of these stories

These three success stories highlight the reality that persistent pain is often the result of multiple factors. In the book Rethinking Causality, Complexity and Evidence for the Unique patient[6], a group of medical researchers, practitioners, and philosophers share a theory, which I believe explains the above stories and the shortcomings of current chronic pain treatment.

The theory is that people have physical, psychological, and social dispositions towards pain, and dispositions away from pain. Persistent pain can thus be the result of an ecosystem of variables, rather than one single cause. Some examples of these “bio-psycho-social” variables are noted in the diagrams below (Figures 1 and 2), with each person’s dispositions a unique combination.

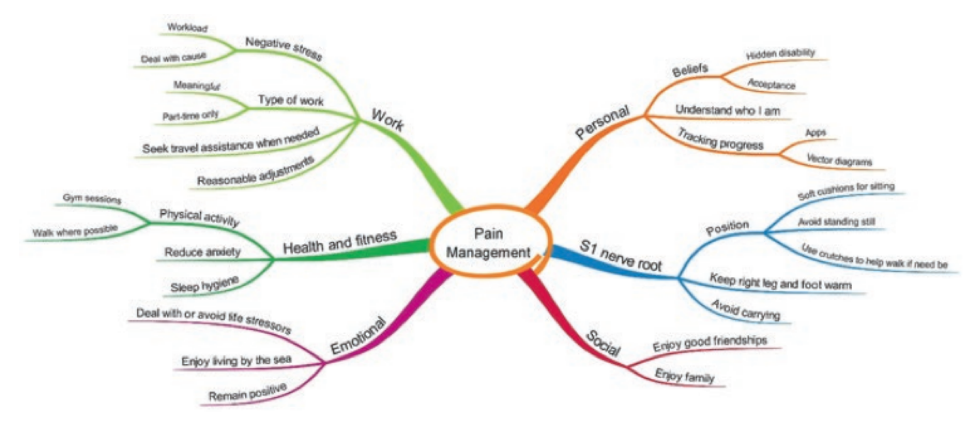

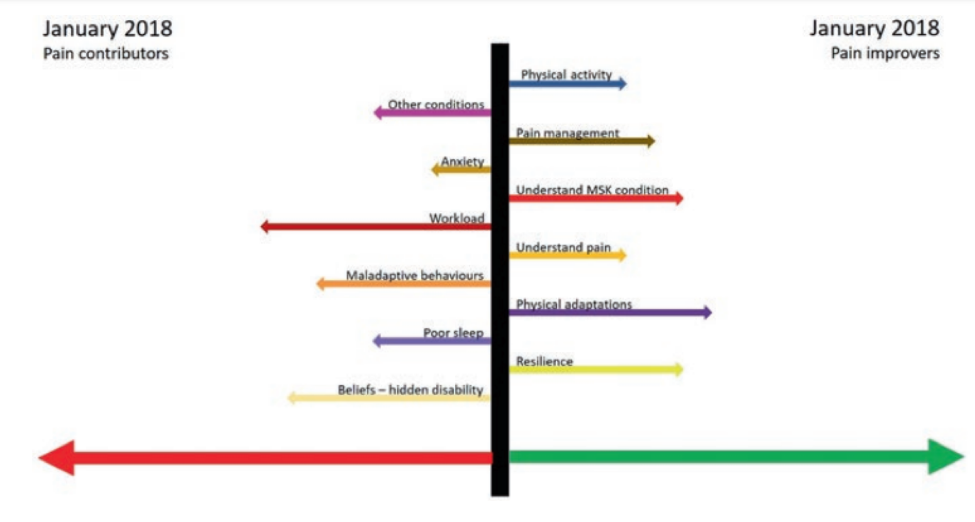

To help identify the relevant dispositions for a particular person, physiotherapist Matt Low suggests bringing together all of the elements of a person’s story with physical examination findings, clinical investigations and the clinician’s views to form a “mind map” (Figure 1). This mind map should be co-constructed by the clinician and the patient. It can then be used to identify a patient’s possible pain contributors and pain improvers (Figure 2).

Fig. 1 An example of a mind map illustrating the complexity of pain (Price, 2020, p. 124)

Fig. 2 An example of a graph illustrating various pain contributor and pain improvers (Price, 2020, p. 125)

Some dispositions have a greater impact on a patient’s experience of pain than others and thus are identified with a longer arrow in Figure 2. Dispositions can also interact with each other to amplify their impact, for example an increase in anxiety might result in poorer sleep. If a patient’s pain contributors outweigh their pain improvers to a great enough extent, pain will be experienced. Conversely, if their pain improvers outweigh their pain contributors sufficiently, pain subsides.

Writing your own success story

If you have undergone all of the recommended medical examinations and treatments, and still have no resolution to your ongoing pain, I recommend taking some time to better understand the different factors that can influence pain, and try rewriting your story with a fresh set of eyes and a dispositional approach.

Further reading

The book, Rethinking Causality, Complexity and Evidence for the Unique Patient, is free online. While the book is written for clinicians, Chapter seven is written by a patient, who does a good job of explaining the dispositional approach in action. Available at: https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-030-41239-5#about

These websites were developed by the National Health Service (U.K.) to provide information for anyone with physical symptoms without an obvious physical cause:

- https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/medically-unexplained-symptoms/

- https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/mental-health/problems-disorders/medically-unexplained-symptoms

References

[1] Dahlhamer J, Lucas J, Zelaya C, et al. Prevalence of Chronic Pain and High-Impact Chronic Pain Among Adults – United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(36):1001-1006. Published 2018 Sep 14. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6736a2.

[2] Finnerup NB. Nonnarcotic Methods of Pain Management. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(25):2440‐2448. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1807061.

[3] Bergman S, Herrström P, Jacobsson LT, Petersson IF. Chronic widespread pain: a three year followup of pain distribution and risk factors. J Rheumatol. 2002 Apr;29(4):818-25. PMID: 11950027.

[4] Sarno, John E. (1998). The Mindbody Prescription: Healing the Body, Healing the Pain. Warner Books. ISBN 0-446-67515-6.

[5] Maund E, Craig D, Suekarran S et al. Management of frozen shoulder: a systematic review and cost-effectiveness analysis. Health Technol Assess. 2012; 16: 1-264; Rangan, Amar et al. Frozen shoulder – Authors’ reply. The Lancet, Volume 397, Issue 10272, 372 – 373.

[6] Anjum, Rani Lill & Copeland, Samantha & Rocca, Elena. (2020). Rethinking Causality, Complexity and Evidence for the Unique Patient A CauseHealth Resource for Healthcare Professionals and the Clinical Encounter: A CauseHealth Resource for Healthcare Professionals and the Clinical Encounter. 10.1007/978-3-030-41239-5.